I first heard No Need To Argue and The Cranberries on a road trip in Australia ’95. My mate had brought it off the back of the single ‘Zombie’ and I liked it instantly before quickly realising I didn’t just like the album, I f**king loved it. Decades later, it’s not just the digital polish that’s sharper — I am. Or at least, I’m smart enough to know why I love it. Back then, I didn’t listen to No Need to Argue just because it was catchy. Sure, it was easy listening, but it was haunting. Unsettling. Beautiful. It made me feel things I didn’t have the vocabulary for. I didn’t understand why I held onto Dolores O’Riordan’s voice, or why her unusual vocal runs and crescendos stuck with me longer than any pop chorus. Now, in my fifties, with years of loss, love, and learning behind me, I hear her voice and lyrics more clearly than ever.

The Cranberries, hailing from Limerick, Ireland, had released their debut album Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? in 1993. The album was initially a slow seller, so much so that the newly signed band’s future was uncertain. But as their relentless touring cycle began, and with an album harbouring incredible songs all the way through, their fan base began to grow dramatically. At the same time, college radio over in America started to pick up on the band. And all of a sudden, The Cranberries were everywhere.

The initial sessions for what would become No Need to Argue commenced at the Magic Shop in New York City. Several of those recordings are featured as bonus tracks on the 30th anniversary release, and are noted as demos. However, producer Stephen Street diplomatically contests that notion. “They’re really alternate takes or works in progress,” he says, noting that the finished versions of those songs were often built upon the basic recordings made in NYC. “We recorded ‘Yeats’ Grave,’ ‘Everything I Said,’ ‘Empty,’ ‘Ridiculous Thoughts,’ and some others there.” Street admits that he helped the musicians sharpen some of their skills and expand their musical vocabulary. “I helped Noel learn the ways of putting a capo on a guitar, and playing in different tunings.” But the band had arrived at the studio with well-developed ideas as to where the music should go. “One of the best things I love about The Cranberries is the ‘space’ that’s there in the music. There was a certain magic they had,” he says.

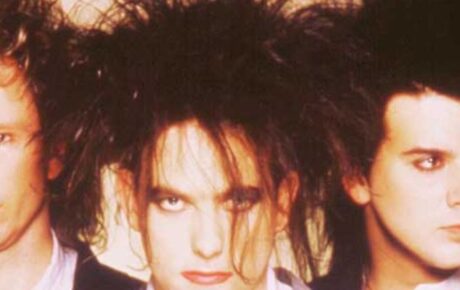

The fans were thirsty for more and it would turn out that their prayers were answered when they returned in relatively short order with their second studio album No Need To Argue in early October the following year of 1994. Upon first listen to the project’s politically charged, guitar-drenched lead single ‘Zombie’, one would have been forgiven for assuming that frontwoman Dolores O’Riordan, brothers Noel and Mike Hogan, and Fergal Lawler, had completely reworked their signature sound for album number two. They would be proven wrong, of course.

Distinguishing their new album from its breakthrough precursor was important to the band, as evidenced in the artwork selected for the album. “The band was very involved in the nature of the images, and wanted to show the difference in appearance of the band between their debut and this second album,” Cally, the band’s art director, explained in the album’s liner notes. “For No Need To Argue, we kept everything in colour, and the previous dark backgrounds were replaced by unashamed whiteness.” Consistent with this about-face in aesthetics, O’Riordan swapped her brown locks for a new bleach-blonde hairdo and she looked as gorgeous as her new music. (I had the pleasure of meeting her briefly in Wellington ’96 outside her hotel. She was unbelievable in her beauty and her humility.)

O’Riordan’s voice is the special sauce for this band. Although their biggest hits were recorded three decades ago, they still brim with contradiction and are fragile but forceful, weary but resolute. Her songs are rarely solutions; they’re emotions laid bare, spilled onto notebooks and translated into songs. The pain is raw, but the presence of that pain is, itself, an act of resistance. Of not turning away. And that’s what makes No Need To Argue so timeless — its refusal to numb itself. Even in its quietest moments, the album burns with the belief that empathy is worth fighting for. No wonder that this record is worth celebrating again. I hear the anguish in ‘Zombie’, which I once sang along to, not fully comprehending the horror she was laying bare. The song wasn’t just a protest, it was a desperate cry against violence, against the erasure of childhood, against generational trauma. A cry that’s gone unheard as the world continues to wage war against innocence.

At the time, ‘Zombie’ acting as a lead single was met with its fair share of obstacles. Due to its cultural and political divisiveness, the band were met with hesitation upon release and the BBC refused to air the music video. But despite all, the track commanded heavy rotation on radio and MTV, priming No Need To Argue to eventually be their best-selling album to date and a huge commercial success.

Musically speaking, however, No Need To Argue did not diverge too far from Everybody Else Is Doing It. Instead, the thirteen-song set produced by their trusted studio confidante Street, whom they admired for his work with The Smiths and Blur, had solidified the group’s strengths as purveyors of melodic, emotive rock-pop of the highest calibre. Largely written while on tour to support Everybody Else Is Doing It in 1993, No Need To Argue found O’Riordan working through the emotional residue of a recent breakup while grappling with her newfound fame. But she also expanded beyond this introspection to examine the events of the world surrounding her, affording the album a broader thematic composition than its predecessor.

‘Zombie’ was the first of four official singles unveiled from the album, immediately followed by the album-opening ‘Ode To My Family’. Written upon “suddenly becoming successful and looking back home and wondering where my childhood went,” as O’Riordan reflected to Rolling Stone, the song is a slow and sombre yet nostalgia-tinted recollection of her youth that finds her reconciling the hardships of the present with those of her past, and specifically the public’s perception of who she is, as evidenced in the song’s second verse – “Understand what I’ve become / It wasn’t my design / And people everywhere think / Something better than I am”.

O’Riordan was just 21 years old when The Cranberries debuted in 1993. She revisits the relationship between her past and present on ‘Twenty One’. The song celebrates the freedom that accompanies the transition from adolescence into adulthood, which can—at least symbolically—protect her from the hardships of the past and help her move on with her life. The tempo picks up with the third single ‘I Can’t Be With You’, a regret-ridden breakup song that finds O’Riordan longing for a past love and the history they shared together. It doubles, however, as a declaration of defiance and independence, as she recognizes that the relationship isn’t designed for longevity and she can’t prolong the inevitable, even though she still harbours strong feelings for her partner.

The symphonic ‘Empty’ continues in the same vein, unfolding as a hauntingly beautiful reflection on regret and loss that leads to hollowed-out emotions, a thematic thread that reemerges later on the plaintive ‘Everything I Said’ and ‘Disappointment’. Not all is doom and gloom throughout No Need To Argue, however, as the endearingly wistful lullaby of a love song ‘Dreaming My Dreams’ is a sanguine, strings-laden dedication to her then-new husband Don Burton, the former tour manager for Duran Duran and The Cranberries’ production manager at the time.

“You wouldn’t believe how many men there are in the music industry who look at a woman in a sexual sense and just want to try it on, to get you into bed,” O’Riordan revealed during a January 1994 Hot Press interview, in describing the impetus behind the fourth and final single ‘Ridiculous Thoughts’. “Even people that you once respected and that you thought valued you because of your mind, your soul, your talent, end up wanting you for only one thing and that really can be disappointing … And worse some of them want to possess you, which is even more frightening.” The supreme highlight of the album, in my opinion, the song’s ethereal intro segues into charging guitar work upon which O’Riordan showcases her vast vocal range, as she exercises the disenchantment that comes with encountering deception and betrayal among people you once trusted.

The album’s most affecting moment arrives with ‘The Icicle Melts’, inspired by the unconscionably tragic 1993 murder of a two-year-old boy (James Bulger) in Liverpool, England. Despite the profound sadness of the song’s subject matter, O’Riordan offers a message of hope and redemption in the chorus, as she sings, “There’s a place for the baby that died / And there’s a time for the mother who cried / And she will hold him in her arms sometime / ‘Cause nine months is too long, too long, too long.”

“We’re not just another pop band,” Lawler (Drummer) insisted to the LA Times shortly after No Need To Argue’s release. “Most pop bands are laughed at; most of them are false people who just want to make money and sell lots of records and that’s all they’re interested in. Then you can go to the other extreme of being so alternative that no one buys your records. Luckily, we’re kind of in the middle. We’re a mix of pop, rock and alternative, I suppose. You can be successful and write really good songs and good music.”

It’s striking how the rerelease of The Cranberries’ work, once considered nonconformist, now finds a renewed place in the mainstream. In an era where much of popular music leans toward polished production, the band’s raw emotional delivery and politically charged lyrics provide a necessary counterpoint. Songs like ‘Zombie’, with its searing commentary on violence and social unrest, resonate powerfully with today’s youth navigating turbulent political landscapes.

Indeed, the really good songs that comprise No Need To Argue solidified the global success that Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? had primed the band for. Thirty years later, it remains one of their finest achievements, an essential component of their discography that concluded with 2019’s In The End, their final studio album and a fitting epitaph for the late, great Dolores O’Riordan. May you rest in peace, we miss you.