Even a godlike genius can use a helping hand from time to time. As part of the Wailers and before the release of Natty Dread, Bob Marley had already put in a considerable effort to break into the charts with his first international album releases Catch A Fire and Burnin’. Those albums, both released in 1973, would eventually be recognised as classics, but neither of them reached the Top 100 in either the US or the UK. The problem which Chris Blackwell and Island Records had to address was not merely that of trying to launch a “new” artist. They were attempting to introduce a whole genre that was still quite alien to the mainstream music media.

It would be overstating the case to say that Eric Clapton’s version of ‘I Shot The Sheriff’ changed everything. But it certainly encouraged a sea change in the popular perception of reggae. Clapton, at this point, was the voice and sound of the mainstream rock establishment. ‘I Shot The Sheriff’ became a US No.1 hit (still Clapton’s only such success) and his enthusiastic endorsement of a Marley song, with an arrangement that did not differ hugely from the original (on the Burnin’ album), was a considerable spur to popular acceptance of reggae music in general and Marley in particular.

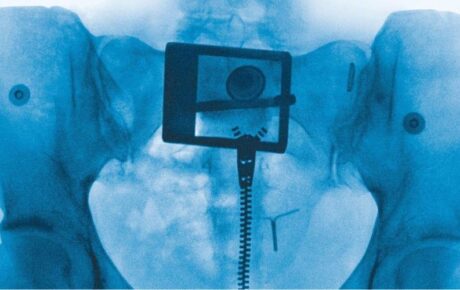

The timing of Clapton’s hit could not have been better. It reached the top of the US chart in September 1974, a month before the release of Natty Dread, the first album to be credited to Bob Marley and the Wailers. With Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer now departed from the group to establish solo careers of their own, Marley took hold of the reins with new confidence and stunning results. Listening now to the opening run of tracks it almost sounds like a Greatest Hits collection – ‘Lively Up Yourself’, ‘No Woman, No Cry’, ‘Them Belly Full (But We Hungry)’ – before you even get to the celebrated title track. ‘Natty Dread’ was a soubriquet Marley had recently acquired on the streets of Jamaica thanks to his lengthening locks which, as could be seen in the cover photograph, were beginning to flow as freely as his music.

The songs were notable not only for the richness of the melodies and wordplay but also for the vitality and imagination of the harmony arrangements which were supplied by a newly-recruited vocal section the I-Threes, featuring Rita Marley (Bob’s wife), Marcia Griffiths and Judy Mowatt. Anyone who feared the departure of Tosh and Wailer might result in a decline in the group’s vocal firepower would have been quickly disabused of the idea by tracks such as ‘Rebel Music (3 O’Clock Roadblock)’ and ‘Talkin Blues’, both of which featured the blues-wailing sound of Lee Jaffe’s harmonica threaded between the haunting vocal chants and call-and-response arrangements.

Another sense in which Natty Dread might have been mistaken for some kind of hits compilation – even in 1974 – was Marley’s and co-producer Chris Blackwell’s continuing policy of re-recording songs that had already been released in previous incarnations of the Wailers. ‘Lively Up Yourself’ had been a single in 1971; ‘Bend Down Low’ had been a hit for the Wailers in Jamaica as long before as 1967, and ‘Them Belly Full’ had appeared earlier as a single called at different times ‘Bellyfull’ and ‘Belly Full’. It didn’t matter a jot to the great majority of fans who were hearing these amazing tunes for the first time, but most definitely not the last.

The rhythm section of the Barrett Brothers, Aston on bass and Carlton on drums, remained gloriously intact and there was a horn section on hand, which arrived like the cavalry to take several of the songs romping home to the finishing post. The melodies were never less than beguiling and if Marley’s voice didn’t get you, his lyrics surely would. ‘Them Belly Full (But We Hungry)’ was one of the several songs that summed up the incredible power of Marley’s music to identify a deep spiritual sorrow or injustice and turn it into the most joyful song. “Forget your troubles and dance” was the kernel of this philosophy. And in ‘No Woman, No Cry’, a reverie about the hardships and emotional bonds forged when growing up with his friends in Trenchtown, he created a song of timeless, evocative power. Or did he?

The songwriting credits on Natty Dread have long been the subject of conjecture. At the time of recording the album, Marley was at loggerheads with his publisher, Cayman Music, a company owned by Danny Sims, who had also been his manager for a while in 1972. In order to avoid any more of his royalties finding their way into the hands of Sims while the dispute remained unresolved, it is thought that Marley assigned several of his own songwriting credits on the album to other people. Thus we find ‘So Jah Seh’ a song that reflected the singer’s growing commitment to the Rastafarian faith, formally credited to Willy Francisco – better known (though not much) as the percussionist Francisco Willie Pep. ‘Natty Dread’, a song in which Marley stood absolutely centre stage as the narrator, was credited to Rita Marley and Allen Cole. Most controversial of all was ‘No Woman, No Cry’, the provenance of which became the subject of a long, ugly legal battle that lasted long after Marley’s death.

There is a school of thought which puts Natty Dread as Marley’s finest album, thus making it “the ultimate reggae album of all time” according to Jim Newsome of allmusic.com. And yet it barely dented the charts, reaching a peak of No.43 in the UK and just scraping in at No. 92 in the US. The truth is, despite Natty Dread’s unarguable classic status, Marley was still only just getting started.

Article originally published on uDiscoverMusic.com.

SEE ALSO: Bob Marley & The Wailers – Live!