Revolver is the Beatles’ seventh studio album, and the album changed everything for the band. The 1966 album sent popular music off its axis and ushered in a vibrant new era of experimental, avant-garde sonic psychedelia, as well as the first use of Indian instrumentation in its tradition in a pop song. Revolver brought about a cultural sea change and marked an important turn in the Beatles’ own creative evolution. With Revolver, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr set about creating musical history.

Revolver was rereleased worldwide on October 28th 2022 in a range of beautifully presented, newly mixed and expanded special edition packages. The new stereo and Dolby Atmos mixes of the album’s opening track ‘Taxman’ make their digital release debuts. Revolver album’s 14 tracks have been newly mixed by producer Giles Martin and engineer Sam Okell in stereo and Dolby Atmos, and the album’s original mono mix is sourced from its 1966 mono master tape. Revolver’s release follows the universally acclaimed remixed and expanded special editions of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (2017), The Beatles (White Album) (2018), Abbey Road (2019), and Let It Be (2021).

View this post on Instagram

All the new Revolver releases feature the album’s new stereo mix, sourced directly from the original four-track master tapes. George Martin’s son Giles Martin is back at the mixing desk for the new Beatles release. Martin credits the technology that Peter Jackson’s audio team used for the Get Back documentary, where they figured out how to properly separate voices from instruments in rehearsal footage, as the catalyst for the project.

In a Variety Magazine interview by Chris Willman, Martin explained how the project came to be. “We did a lot of work on this for Get Back and luckily, thanks to the pandemic, because it slowed the whole project, a lot more people spent more time in their rooms working on stuff than they would’ve done normally, and Peter’s team started making these breakthroughs. I was working with them. I said, “Look, should we try doing Revolver? We started looking at that, and eventually we had all the ingredients, so I could mix it. It was as simple as that.

That Taxman track, which I’m using as a demo, has guitar, bass and drums together; I can take off the guitar, I can take off the bass, and then I can even separate the snare drum and kick drum as well. And they sound like the snare drum and kick drum. There’s no hint of guitar on there (even though they’d been baked together on the master tapes). And I don’t know how it’s done! It’s like I’m giving them a cake and they’re giving me flour, eggs, and milk and some sugar.” The new AI technology was created by the award-winning sound team led by Emile de la Rey at Peter Jackson’s WingNut Films Productions Ltd. in Wellington, New Zealand.

The Beatles’ material recorded from 1967 onwards was done using eight tracks to capture separate elements of the recording. But prior to and including 1966’s Revolver, all the albums were created on four tracks, separating the instrumentation and vocals that had been compressed from four tracks into two track masters. It would have been impossible without the AI technology created for Get Back.

The audio on Revolver is brought forth in stunning clarity with the help of this cutting-edge demixing technology. In a recent interview with Wellington composer Stephen Gallagher, who recently won an Emmy award for sound editing on Get Back, Gallagher commented on having heard the new mix of Revolver in Los Angeles at Giles’s invitation.

“The mixes allow you to enjoy elements of the songs that you have never heard before. There is a new clarity without losing any of the magic that was captured on the original recordings.” The physical and digital Revolver super deluxe collections feature the album’s original mono mix, 28 early takes from the Revolver sessions, and three home demos, and a four-track EP with new stereo mixes and remastered original mono mixes for the singles ‘Paperback Writer’ and ‘Rain’. But what is it about Revolver that makes this album so special? When I posed this question to Gallagher, he said, “It’s just such a wonderfully unique album. When I got my first copy as a teenager, I listened to it every day for years! This album had a huge influence on me as a musician. You cannot ignore the significance of the historical timeline of the band and how, in their mid 20s, the Beatles were searching for and finding a new voice”.

The summer of 1966 in London was one for the history books, especially as far as the social evolution of youth and counterculture are concerned. But never more so than for the Beatles. The band was coming of the back of the wildly inventive sonic statement that was Rubber Soul. The album remained in the UK Top 10 till June, 1966. The influence of Rubber Soul inspired Brian Wilson of The Beach Boys to respond with their legendary 1966 album Pet Sounds.

Revolver is the Beatles shedding their teen idol image and their first step forward as seriously creative musicians. As it would turn out, 1966 would be the year of many lasts for the Beatles. Significantly, on 1 May, the band played their last UK conventional live concert at Empire Pool (Wembley Stadium) alongside The Who and The Rolling Stones. Unbeknownst to them at the time, when the Revolver recordings finished, the band would embark on their last concert tour as well and play their last stadium concert ever on 29 August at Candlestick Park in San Francisco.

Early in 1966, their manager, Brian Epstein, wanted the band to make a sequel to the wildly successful movie, Help. The movie was going to be based on a book called Talent for Loving by Richard Condon, published in 1961. However, the band would reject the script and premise for the movie, which was later made without the Beatles in 1969 and with Richard Quine directing. The decision to abandon the sequel gave the Beatles the longest break they had ever had, and Epstein had nothing planned for the band, giving them a three-month break. This would be the first significant break for the band since they started their recording contract in 1962. The reprieve in their schedule would prove to be one of their most auspicious decisions. Due to the accumulating fame and the attention that was surrounding them, the band was beginning to show the signs of splintering as a unit.

View this post on Instagram

During January, February, and March of 1966, each member had the opportunity to explore their own artistic visions and intellectual interests. Everyone in the band at that point owned their own home and were married, except for McCartney, who bought a house in London’s St. John’s Wood area, close to what would become Abby Road Studios, otherwise known at the time as St John’s Wood Studio. McCartney, with his partner at the time, actress Jane Asher, began to explore the art scene in London. McCartney became very influenced by the new and experimental ideas of the avant-garde art scene. He began broadening his artistic horizons by attending many live concerts and galleries with Asher involved with the avant-garde scene in London.

Lennon took the opportunity of zero commitments to explore his interest in counterculture and the expansion of his mind through taking acid. He started dropping acid by himself at home in his search for a new religious consciousness through a transcendent mystical experience, as well as reading books like The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead by Timothy Leary (PhD) and Ralph Metzner (PhD).

Harrison dived headfirst into his love of Indian culture and spiritualism over this period. He spent this time with his friend, the revered sitar player, Ravi Shankar. Both Lennon and Harrison had begun their experimentation with the drug, LSD, in 1965. Through these experiences, the two musicians developed a fascination for Eastern philosophical concepts, particularly regarding the illusory nature of human existence. They both built home recording studios and installed Brunell tape recorders. Lennon also bought himself a Mellotron MK2, which is a lavish investment at a cost of a £1,000, that is about US $22,000 in today’s money.

The Mellotron had a range of sampled sounds stored on magnetic tapes that had been recorded at IBC in 1964. Lennon was intrigued and impressed with the instrument and immediately ordered one in black. The instillation of these recorders allowed Lennon and Harrison to experiment with different instruments and sounds in their home studios, which would later help shape the musical collage found on Revolver. During the same period, Starr equipped his house in Weybridge with many luxury items, including numerous televisions, light machines, film projectors, stereo equipment, a billiard table, a go-kart track, and a bar named the Flying Cow. Starr did not include a drum kit in the house. He explained, “When we don’t record, I don’t play.” However, what follows as the band returned to studio at the beginning of April, fresh and inspired, is nothing short of extraordinary.

View this post on Instagram

By 1966, being a Beatle was a complicated landscape to navigate with many moving parts. One of these parts is the band coming to the end of their 1962 EMI recording contract. The Beatles, at the time, were only paid a pathetic one penny for each album sold. That penny was then divided 4 ways between each member and then halved again for overseas collection. The government was also taking 96 per cent of their earnings, making the Beatles a hot commodity and a valuable cash cow. The band were more than ready to be freed from these shackles, along with many others, before the year was out. The end of the contract would be the catalyst for the creation of Apple Corps Ltd., allowing the Beatles more creative and financial freedom.

EMI, to their credit, had given the band an unprecedented three months to record their next album beginning on 6 April and concluding on 21 June 1966. This is a far cry from the one day they were given to record Please, Please Me in 1962. The Beatles at this time were at the height of their creative powers and ready to collectively bring together their increasingly individual creative slants to the studio and collectively run them through the filter that is the Beatles. However, Lennon was less than enthused about being a Beatle at this point in his life and was experiencing increasingly longer and longer spells of depression.

Compounded with a growing interest in drug experimentation, Lennon was not in great shape. Therefore, he started loosening his grip on the creative rains of the band and allowed McCartney to take more control of the band, while Harrison also ceased his opportunity to flex his song-writing skills, which culminated in him bringing three tracks to the finished album for the first time. At the same time, Ringo Starr was wanting to experiment with a new sound and expression for the drums on the next album. The album was to be mostly recorded with George Martin in Studio Three at the EMI Studios (now called Abbey Road Studios) in London. The scene is set for what would be one of the most unique and celebrated albums the band would ever record. It was to be a truly mind-blowing sonic experience for the fans. Nothing could have prepared the world for what the band had to offer when they released Revolver.

View this post on Instagram

Revolver was not the first title that was considered by the band for the name of the record. Lennon had wanted to call the album Abracadabra or Four Sides of the Eternal Triangle. Ringo had suggested calling the album After Geography, in response to the recently released Rolling Stones’ album, After Math. Other suggestions were Beatles on Safari and Magic Circles. The band eventually settled on Revolver because they wanted a title that represented what the record literally does, which is revolve.

Revolver was originally scheduled to be recorded in Nashville, Tennessee. However, George Martin and the band decided to stay in more familiar surroundings, and on 6 April 1966, the Beatles gathered in Studio Three at EMI St. John’s Wood Studios for their first Revolver recording session. Producer George Martin was flanked by recording engineer Geoff Emerick and technical engineer Ken Townsend, and it was the beginning of 220 hours of recorded studio time. Moreover, Gallagher also reflected in his interview that one of the most remarkable aspects of the album’s sound is that George Martin was so open to creative experimentation.

“Nothing was left off the table creatively and everyone was open to hear and bring the creative ideas to a fruition. This is more unusual than one may think. Even today, having that kind of creative freedom can be rare. Then when one considers that this is a commercially successful band at the height of their career, Martin’s receptiveness to their creativity is crucial to the success of those recordings.”

Moreover, Giles Martin also commented on the creative freedom his father brought to the studio in his Vanity Fair interview: “He managed to pull in everything they wanted and filter it onto a disc. Whether it’s the French horn on ‘For No One’ or the horn arrangement on ‘Got To Get You Into My Life’ or the string arrangement on ‘Eleanor Rigby,’ you can tell how open minded he was as a producer compared to a lot of other producers that would say, ‘No, we need more hits.’ They never had that discussion. They were like, ‘How different can we make every song?’ — whether it’s ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ just as a drone in C to ‘Here, There and Everywhere’, which is obviously a complex, rounded song. I think that probably his musicality and open mind are what stand out.”

It is also 19-year-old Geoff Emerick’s contribution to the recording sessions for Revolver that is the essential special sauce. The Beatles’ recording engineer up to that time had been Norman Smith, who Lennon nicknamed “Normal.” Smith had been promoted by EMI to a record producer. Martin had become acutely aware of the band’s growing palate for musical exploration and the technical challenges that this would bring to the recording studio. He found exactly what he needed in the young Emerick. Emerick was fond of claiming that he had merely been in the right place at the right time. His career had begun as a lowly teenage button pusher at EMI studios in the early 1960s.

Emerick threw himself wholeheartedly into the new venture with the Beatles. Some of his innovations were straightforward. Recognising that the power of Starr’s drumming was poorly represented on record, he broke the studio’s long-held rules about how to record drums, shoving microphones closer to Starr’s kit than had previously been allowed, thus conjuring up the thunderous, propulsive – and regularly imitated – drum sound. He found the enormous four-neck sweater that the whole band had worn in their 1965 Christmas special lying around the studio and stuffed the seater into Starr’s bass drum to dampen the sound. He also put a mic above the kit as well as a second mic three inches from the drum to heighten the drum sound in the recordings; he then put the sound through a Fairchild 600-valve limiter and compressor. This was an unconventional recording technique for drums that gave the instrument a deeper sound.

Emerick’s youth and lack of need for conformity in the studio proved remarkably adept at translating the Beatles’ more whimsical ideas into reality. In retrospect, it cannot be overstated how crucial and poignant young Emerick’s contribution was to the recordings of Revolver. Moving forward he would remain a crucial part of the Beatles’ sound for the remaining three years of the band’s recording career.

View this post on Instagram

On 10 June in the UK and 10 May in the US, the band would release their first single for the year that was also recorded during the Revolver sessions. It was a double-sided seven inch consisting of two songs by Lennon/McCartney. McCartney’s song ‘Paperback Writer’ was a transitional song more in vain of their previous effort in Rubber Soul. It also announced a new sound for the band, and specifically McCartney’s bass sound. During this time, McCartney stopped playing his famous Hoffner bass and moved to playing a Richenbacker 4001S bass guitar. The new bass had more treble sound and a better action to allow McCartney to play crazy riffs on it. The bass was also played through a loud speaker and then into a microphone, which gave a much punchier sound to the bass throughout the entire record.

This was also the first time the Beatles used automatic double tracking (ADT) that gave their sound a thicker tone. The technique was created by studio engineer Ken Townsend, and later could be heard being used very effectively on Queen’s backing vocals on ‘Bohemian Rapsody’. It was also the first time the band used headphones during the recording process. Prior to this, when the band was over dubbing, they would listen to the playback through speakers that would be picked up by the live microphones in the studio, creating leakage between tracks.

‘Paperback Writer’ was an ode to the up and coming artists at the time who came from less-privileged backgrounds; hence the title ‘Paperback Writer’ as opposed to ‘The Novelist’. McCartney cleverly uses word play within the lyrics that gain momentum throughout the song to emphasise this point. ‘Paperback Writer’ was well received and went on to top the singles’ charts in the United Kingdom, the United States, Ireland, West Germany, Australia, New Zealand, and Norway. The song was a statement of where the band was at the time and a shot across the bow of their contemporaries as to what was about to come.

View this post on Instagram

The companion piece to the single was Lennon’s song ‘Rain’, which he described as meaning, “It’s about people moaning about the weather all the time.” The song is an attempt by Lennon to express the heightened experience of being under the influence of LSD, and he wanted to capture the atmosphere of how the weather felt, trying to capture the new idea of psychedelic consciousness. This can been seen as the birth of psychedelic music, and many bands would follow in his footsteps.

The song has a very us verses them nature to the lyrics as the social landscape changes. He wanted to express more of a delineation between the hip people using drugs and the straight people who are caught up in their material lives and missing the beauty around them as it passes them by. The recording of the song is the first example of the band’s use of various speeding or varispeeding, where they have the ability to speed up or slow down the recording in playback. The backing track to the song is recorded at a very fast tempo and then the playback is slowed to give a very shimmering feel to the song. Moreover, Lennon’s vocal is recorded slower and then speeds up.

McCartney plays a stand-out bass part on this song, with his new Rickenbacker having the most beautiful melodic undertones, giving a distinct Indian texture. The other stand-out element of this song is the use of backward vocal tracks. How the vocal track came to be comes from differing recollections. Lennon claimed that one night he came home from the studio and was high and wanted to listen to the song. He accidentally put it in backwards. He was so taken with the sound that he wanted to put it in the song. However, when George Martin commented on his recollection of the use of backward vocals, he stated that he thought it would be interesting to put a backwards vocal on the track. He took a snippet of Lennon’s vocal from the beginning of the song and reversed it.

It’s hard to say who is correct in their recollection. However, Lennon is often quoted as saying, “I don’t remember the 60s very well, as I was there.” In the US, the song peaked at number 23 on the Billboard Hot 100 on 9 July 1966 and remained there the following week. Today, Lennon’s ‘Rain’ is still finding notoriety on many noted greatest songs of all time lists.

The Revolver album was released in the UK on 5 August 1966 and then released three days later in the US with a different track listing. Lennon’s ‘I’m only Sleeping’, ‘Your Bird Can Sing’, and ‘Dr Robert’, were left off the US release as they were recorded earlier in the sessions and were added to the US release of the Yesterday & Today compilation. Revolver was also released just before the Beatles completed their final tour in the US.

The album draws a musical line in the sand, revealing them as studio innovators. Even before the listener removes the vinyl from the sleeve, the cover art itself gives the impression that this is not a repeat of the previous Beatles album. It is the second time in a row that the band chose not to have their name on the album cover, just like they did for Rubber Soul. This is perhaps a reflection of where they saw themselves as artists and the desire to have the listener focus on the collective musical statement rather than on themselves.

The cover art for Revolver was created by German-born bassist and artist, Klass Voormann, one of the Beatles’ oldest friends from their time in Hamburg during the early 1960s. Voormann’s artwork was part line drawing and part collage, using photographs mostly taken between 1964 and 1965 by Robert Freeman. In his line drawings of the four Beatles, Voormann drew inspiration from the work of the nineteenth-century illustrator, Aubrey Beardsley, who was the subject of a long-running exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 1966, and was highly influential on fashion and design themes of the time. During the creation of the cover, Voormann struggled to capture Harrison’s likeness with his line drawing, resorted to cutting out his eyes and lips from a photo session with Freeman, and glued them on to better capture his likeness.

View this post on Instagram

His use of black and white motifs was also a rebellion against the fashionable psychedelic covers of the time. Voormann placed the various portions of the photos within the tangle of hair that connects the four faces. The tangled hair has also been interpreted as a visual representation of all members of the band acting as a singular unit. Over time, it has also been speculated that the pencil drawing relates to the lyric “avalanche of thoughts” in the George Harrison song ‘I Want To Tell You’ with ideas spewing forth from the mind.

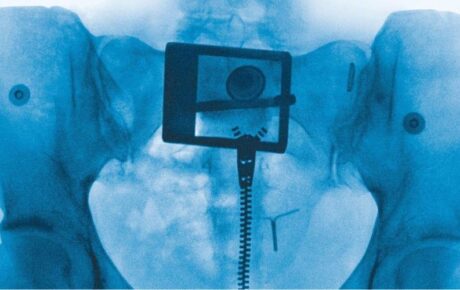

The back cover photo was part of a series taken by Robert Whitaker during a filming session at EMI Studios. During the same photo shoot, Whitaker also took pictures of the Beatles, examining orange transparencies of their infamous original “butcher” cover design for the US release of Yesterday and Today, which are remembered primarily for the controversy surrounding its original cover image, taken by Whitaker. It depicts the band dressed in white coats and is covered with decapitated baby dolls and pieces of raw meat. Although the photo was intended to be part of a larger work critiquing the adulation afforded to the Beatles, the band members insisted it was a statement against the Vietnam War. Due to the controversy, the cover would later be changed to a more palatable photo of the band surrounding a large steamer suitcase. The back photo on Revolver also demonstrates the Beatles’ adoption of fashion from boutiques that had recently opened in Chelsea, further demonstrating the cultural shift that took place within and around the band. For his troubles, Voormann was paid £40 and also won the Grammy Award for best album cover/graphic arts in 1967.

View this post on Instagram

Revolver opens for the first time with a Harrison song titled ‘Taxman’. Harrison contributed three songs to Revolver. The subject matter for ‘Taxman’ is ground breaking. It is a socio-political commentary on the state of the tax system in the UK at the time and protested the high marginal tax rates paid by top earners like the Beatles. At that time, the United Kingdom was under Harold Wilson’s Labour government (both Harold Wilson and Ted Heath, the leader of the conservative party, get a mention in the lyrics). The song illuminates the toll these taxes had impacting himself and other musicians. The song’s count-in is out of tempo with the performance that follows, and in many ways is esoterically introducing the flavour of the album. A stand-out moment in the song is McCartney’s guitar solo, which is a homage to Harrison’s eastern sensibilities and is inspired by traditional Indian melodies. The outcome is a guitar solo that sounds nothing like anything else in recorded history at the time.

Unsurprisingly, in his second composition, Harrison continues the Indian theme with ‘Love You To’. The track is also inspired by Harrison’s experimentation with LSD. The working title for this was originally ‘Granny Smith,’ named after the apple, which later became the image for Apple Corp. His interest in the sitar and love of Indian music came from a sound playback in a restaurant scene during the filming of Help. He was fascinated and quickly became a student and acolyte of the sitar master, Ravi Shankar.

‘Love You To’ is part love song and part philosophical statement. Harrison and McCartney are the only contributors to the track. Harrison plays the sitar acoustic guitar and a fuzz tone effect electric guitar for the basic track, with McCartney on backing vocals and Anil Bhagwat of London’s Asian Music Circle playing tabla. The song is very authentic to Indian classical music in its structure. It starts with an improvisatory opening called the Alap. Then the song increases the tempo to what is called the Gat, which means composition or form. Harrison is following the form of Indian classical music which embodies his respect for the music’s origins. The song is seen as the first conscious attempt in pop to emulate a non-Western form of music in structure and instrumentation. The ideologies of eastern philosophy also align well with the counterculture of the day.

‘I Want to Tell You’, Harrison’s last contribution to Revolver, is about “the avalanche of thoughts” that he found hard to express in words. The imagery that this quote conjures up is visually expressed by Klass Voormann’s album cover art. The working title for this song was ‘Laxton’s Superb’, which is another classic and popular English-style variety of apple from the late Victorian period. The track opens with a fade in that works well within the context of the song and the inability to say what you want to say. This is bookended with a fade out for the diminuendo at the end.

Harrison, as a song writer, has a unique ability to reflect the meaning of the song within the music as well as the lyrics. He uses a jarring dissident chord at the end of every verse, helping the music reflect what is being expressed in the lyrics. McCartney adds a one-note piano part that adds to the theme: the hesitation of not being able to say something. The prominent backing vocals from Lennon and McCartney include Indian-style gamak ornamentation in McCartney’s high harmony, similar to the melisma effect used in ‘Love You To’. The three songs by Harrison herald him as a significant song writer in his own right. His deep interest in Indian culture would continue to permeate its way into the rest of the band, culminating in the famous trip to India to meet the Maharishi in February 1968.

View this post on Instagram

McCartney’s first song on Revolver is ‘Eleanor Rigby,’ which is a song that deals with the themes of depression, loneliness, death, and existential drama. The story involves the title character, Eleanor Rigby, who is an aged spinster, and a lonely priest named Father McKenzie, who writes “sermon[s] that no one will hear.” He presides over Rigby’s funeral and acknowledges that despite his efforts, “no one was saved.” Coincidently, the original name for the title character was going to be Miss Daisy Hawkins. However, when McCartney visited Bristol to see Jane Asher in a play called ‘The Happiest Days of Your Life,’ he happened upon a wine and spirits store called Rigby & Evans and was enchanted with the name Rigby, and combined this with the name of the actress Eleanor Braun from the movie Help to create the song’s title.

Moreover, Father McKenzie was originally to be called Father McCartney. However, Lennon’s friend, Pete Shotton, pointed out that people might think he was referring to his dad. McCartney then opened a phone book and found the name McKenzie, which he liked and decided on that. In a strange twist of fate at St. Peters Church in Wilton where McCartney and Lennon first met, there was a grave marker to a woman called Eleanor Rigby. ‘Eleanor Rigby’ was the first McCartney composition to depart from the themes of a standard love song. The lyrics were the product of a group effort, with Harrison, Starr, Lennon, and Shotton all contributing. Lennon and Harrison supplied harmonies alongside McCartney’s lead vocal. It was also Harrison who contributed the line “all the lonely people.” None of the band members played on the recording; instead, Martin arranged the track for a string octet (or double quartet) after McCartney had been inspired by listening to recordings of the composer Antonio Vivaldi with Asher. Martin, when scoring the octet track, wanted a more strident sound and drew inspiration from Bernard Herrmann’s 1960 film score for Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.

View this post on Instagram

McCartney’s next contribution to the album is the beautiful ballad ‘Here, There and Everywhere’. It took three days to record the song due to the stacked vocal sound that was inspired by the song ‘God Only Knows’ from the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds album. McCartney’s double-tracked vocal was treated with varispeeding, resulting in a higher pitch at playback. The song’s opening lines are sung in free time before its 4/4 time signature is established; it prepares the listener for the most striking and expressive tonal events. The song was one that the whole band liked. This was not always the case, and Lennon, in particular, had no problem with telling the band which songs he didn’t like.

Opening side B is McCartney’s ‘Good Day Sunshine’. It is an ode to the incredible weather that was experienced in the UK during the summer of 1966. McCartney’s piano playing dominates the recording and the verses reflect aspects of vaudeville composition. George Martin plays the piano solo on the track, which recalls the ragtime style of Scott Joplin. Once again, the solo was recorded slowly and then sped up. The song ends with group harmonies repeating the title phrase. The song was recorded very quickly and then the overdubs were added, and the backing-track version on the album was the original first take.

‘For No One’ was written by McCartney in Switzerland while on holiday with Asher and was inspired by their relationship. Given the theme of loneliness in the lyrics, it leads one to speculate that it wasn’t going so well. Along with ‘Good Day Sunshine’, McCartney similarly omitted guitar parts for Harrison and Lennon. He would continue eschewing the group dynamic when recording his songs, a trend that would prove unpopular with his bandmates in later years.

McCartney plays piano, bass, and clavichord (which he rented for the session for five genies, approximately half a pound in today’s currency), with Starr on drums and percussion. Continuing with his fascination with classical music, McCartney wanted a French horn to the track. The overdubbed solo was added by Alan Civil, the principal horn player for the London Philharmonic Orchestra, with little guidance from McCartney or Martin. Civil recalled having to busk his part. The vocal track was recorded then speed up, and the backing track was recorded faster and slowed down, which left the tuning somewhere between a B flat and B major; therefore, Civil had to tune his French horn to the song.

When Civil first saw the song title, he thought it was ‘For Number One’. The original title was ‘Why Did It Die?’. The song has such a sweet melody line while the lyrics reflect the heartbreak of still being in a relationship that both parties know has concluded. It is McCartney’s first mature love song and was recorded in ten takes.

McCartney’s final song on Revolver, ‘Gotta Get You into My Life’, is his ode to marijuana (McCartney didn’t experiment with acid until 1967). He wanted to write a Motown-style song after seeing Stevie Wonder perform at the Scotch of St. James nightclub in February 1966. In order to create this sound, they recorded with three trumpets and two tenor saxophones, played by two members of the Blue Flames and other session musicians. In another inspired moment by Emerick, he put the microphone down on the bell of the instrument, which was very unusual.

The horn parts are superimposed on the track with a slight delay, thereby doubling the presence of their contributions. Usually, when recording a horn section, the microphones are approximately six feet away to encapsulate the entire sound, but Emerick wanted to really control what the listener experienced. This took out all the ambience from the sound and then heavily compressed it, giving a really punchy sound horn section.

In keeping with the rest of the album, the band wanted the instruments to sound nothing like they should and created their own sonic world. The band would record many versions of the song before settling on the final version. McCartney’s songs on this album make a very individualised creative statement that has become his calling card of beautiful melodies intertwined with evocative imagery and emotive-laden lyrics.

Lennon/McCartney continued their theme of composing a song for Starr to sing lead vocals with ‘Yellow Submarine’. It was a children’s song that would also tap into a new audience of the younger generation and later became the subject matter of their animated film of the same name. The song tells the story of life on a sea voyage accompanied by friends. The track itself sits well within the overall track listing and sonic diversity of Revolver, adding yet another dimension to the many layers of the glass onion that is found on the album.

The song is mostly composed by McCartney, with the Scottish singer Donavan contributing the line “Sky of blue, sea of green,” which rhymes nicely with submarine. It took one day to record the basic track, and on 1 June the Beatles, led by Starr and a few of their friends, enhanced the festive nautical atmosphere by adding sounds such as chains, bells, whistles, tubs of water, and chinking glasses, all sourced from Studio Two’s trap room. It was a who’s who of the British music scene at the time with Brian Jones, Marianne Faithful, Patty Boyd, George Martin, Brian Epstein, Jeff Emerick and Mel Evans, the band’s tour technician, all contributing backing vocals. Lennon then went and sat in the EMI Studio’s echo chamber behind Studio Two to add the backing vocal effects such as “full steam ahead” and double tracked the effect alongside Ringo on the chorus. ‘Yellow Submarine’ is the only single to be released from the album as a double side A with ‘Eleanor Rigby’ on the flipside, which was released on the same day as the album in the UK.

Lennon’s first contribution to Revolver is ‘I’m Only Sleeping’. It was half an acid dream and half laziness (which Lennon was well known for) and a candid confession from Lennon. Continuing with his experimentation of varispeeding, as with ‘Rain’, the basic track was recorded at a faster tempo then slowed down. Lennon’s vocal track was recorded, slowed down, and then sped up for this song along with ADT as he sought to replicate a “papery old man’s voice.” Starr’s cymbal splashes are slowed down, giving a dreamy element to the track. Harrison’s guitar solo was composed forwards and then Martin transcribed it backwards. He then recorded himself playing it backwards, reversed it, and dubbed the reverse/forward guitar solo into the track. The effect is that Harrison is playing the correct notes forward, but it sounds backwards, and this whole process took 6–9 hours to complete.

Lennon’s next song is the side closer to side A. ‘She Said, She Said’ once again has its inspiration drawn from Lennon being on an acid trip and his experimentation with the drug on their 1965 tour in the United States. During the tour in August, Brian Epstein had hired a house for the band in Los Angeles, where infamously, John and George had taken acid with Peter Fonda and some members of the band, The Byrds. Fonda had been describing a near-death experience he had as a child when he accidentally shot himself in the chest with a shotgun. This freaked Harrison out, and Lennon had him removed from the premises as his story was ruining their trip.

The structure of the song is very simple with the only outstanding effect being a fuzzy guitar note throughout the song. It also marks the second time that a Beatles’ arrangement uses a shifting metre. McCartney has stated that he didn’t play bass on the song as he left the studio after a disagreement with the band, so Harrison played bass instead, in addition to lead guitar and harmony vocals. This is the last song recorded for the album.

The working title for Lennon’s ‘And Your Bird Can Sing’ was ‘You Don’t Get Me’. It was a song Lennon had written for hip people. Lennon sings to someone who has seen “seven wonders” yet is unable to empathise with him and his feelings of isolation. It has often been compared as a companion piece to ‘Rain’ with the similar us versus them theme. Lennon described the song as “fancy paper around an empty box”. It is well documented that Lennon did not like the song.

‘And Your Bird Can Sing’ was directed by Frank Sinatra after Lennon had read a hagiographic article on the singer in Esquire magazine, in which Sinatra was lauded as “the fully emancipated male… the man who can have anything he wants”. The song was recorded in two 12-hour long sessions with minimal breaks. McCartney and Harrison played a dual guitar part with one guitar capo on the second fret and the other guitar open with nearly matching musical structures. They were both playing their Epiphone Casino guitars.

‘Dr Robert’ was also written by Lennon, although McCartney has since stated he co-authored it. Dr Robert Freeman was an Austrian physician in New York who was known for dispensing vitamin B12 injections, heavily laced with amphetamine, to his patients. One of those patients was Jackie Kennedy. He created a market for himself by getting his patients addicted to his vitamin shots and was debarred in 1977. The backing vocal track suggests a choir praising the doctor for his services. The song structure is interrupted by two bridge sections over harmonium and chiming guitar chords. It is a simple song composition with an exceptional lead guitar part from Harrison, giving a country-western-meets-the-Sitar-feel to the recording.

Finally, Lennon’s masterpiece of the album, ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ was the first track recorded during the Revolver sessions. The Beatles went into the studio blazing! The song had the working title ‘Mark 1’ and later ‘The Void’. However, Lennon would later settle on the title ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, which was a turn of phrase that Starr used to use at the time. The song is the stand-out sonic statement on the album, and to this day, is still revered by many as one of the greatest songs ever recorded. As Gallagher stated in his interview, “Hearing that song for the first time was mind blowing.”

The recording includes reverse guitar, processed vocals, and looped tape effects, accompanying a strongly syncopated, repetitive drum beat. The song’s harmonic structure is derived yet again from Indian music and is based on a high volume C drone played by Harrison on a tambura. The song contains five tape loops; the first sounds like a seagull, which is a recording of Paul laughing and then sped up; the second is an orchestra chord in B flat major taken from a piece of vinyl owned by McCartney, and is one of the earliest examples of sampling; the third is a guitar in C flat major played at double speed and then reversed; the fourth is a recording of mellotron voicing believed to be on strings and brass setting; the fifth is a distorted sitar that can be heard following the instrumental break accompanying the line, “Is it being, it is being.”

The recording of these five tape loops had to be done by playing all five simultaneously against a backing track. The recording session was like a performance with the band, along with Martin and Emerick manning the faders on the mixing desk, bringing the separate tracks up and down while the backing track was playing. The mixing desk becomes an instrument, and given the complexity of this process and the technological restrictions of a four-track recording studio, this was done in one take and can never be repeated again.

The lyrics for ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ are adapted from the book The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead by Timothy Leary (PhD) and Ralph Metzner (PhD). When the full lunacy of Lennon’s initial plans for ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ were unveiled, Lennon apparently wanted the vocal to sound like “the Dalai Lama and thousands of Tibetan monks chanting on a mountain top.” It was Emerick who suggested a more workable solution to creating an otherworldly sound by physically dismantling a Hammond organ so that Lennon’s voice could be fed through the rotating speaker in its cabinet that gave the instrument its distinctive tremolo effect. The song has no harmonies—just a constant drone of a F on a tambora. Lennon later grumbled that they should have just hired the Tibetan monks. Retrospectively, the listener can hear elements of this track on every other song on the record. These first recording sessions paved the way for a cascading flow of innovative studio techniques and effects that would separate the boys from Liverpool from the rest. Bob Dylan made the comment when he heard the song, “Oh, I get it. You don’t want to be cute anymore.”

View this post on Instagram

Revolver was released a few days before the Beatles completed their final tour. It was little surprise that the Beatles were not concerned how they would play the Revolver material live, as it was never to be played live. It is well documented that the band, and in particular George, did not want to tour anymore. The last few tours had been full of controversy. The combination of off stage dramatics and not being able to hear themselves play on stage led to their decision to retire from touring following the end of their North American tour.

Touring at the time, as it is now, was seen as essential to a band’s financial stability and success as well as keeping the band in the public consciousness. The decision was also fuelled by the reaction to Lennon’s comment in the Evening Standard on 4 March 1966 where he proclaimed, “We’re more popular than Jesus.” The press conferences during the tour were typically focused on religious matters from that point forward rather than the band’s new music. When given context, this statement by Lennon was merely expressing how it felt to be a Beatle at the time. However, the reaction in the US was nothing short of condemnation. This simple faux pas would result in many large protests and the mass burning of Beatles’ albums, especially in the bible belt regions of the United States. Revolver also marked the start of a change in the Beatles’ core audience, as their young, female-dominated fan base gave way to a following that increasingly comprised more serious-minded listeners.

The album received critical success across the board. Peter Clayton, a jazz critic for Gramophone magazine, described it as, “an astonishing collection” that defied easy categorisation since much of the LP had no precedent in the context of pop music. Clayton concluded, “If there’s anything wrong with the record at all, it is that such a diet of newness might give the ordinary pop picker indigestion.”

Revolver entered the UK charts at number one and stayed there for seven weeks during its 34-week run in the Top 40. By October 1966, at least ten of the LP’s songs had been covered by other artists. Despite the controversy in the US, Revolver hit number one on 10 September, a week after the end of Yesterday and Today‘s five-week run at the top. Revolver has also been recognised as having inspired many new subgenres of music, anticipating electronica, punk rock, baroque rock and world music, among other styles. In 1999, Revolver was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, an award bestowed by the American Recording Academy to honour recordings of lasting qualitative or historical significance that are at least 25 years old.

View this post on Instagram

Now, in 2022, the vaults have been reopened and the masters have been dusted off for a new generation of listeners to enjoy. When asked about the old Beatles fans verses a new generation’s possible reaction to the release of Revolver, Giles Martin commented, “I love the fact that there’s forums going. I’m never gonna listen to anything Giles Martin does. It just means they’re just passionate about stuff. I have no issue at all. I think it’s great. They’re the ones listening to the stuff. It’s all the people that aren’t listening to the albums that I want to get to, and every single Beatles project is the holy grail of someone.”

And as to the question of whether Revolver is the Beatles’ greatest album. Martin stated, “I’ve never been very good at the (comparative album) stuff because my background was doing Love (with his father in the 2000s), and Love was just basically all of the Beatles, if that makes sense… You could argue they were peaking on Abbey Road; the second half of that record is just amazing. Their most popular song is ‘Here Comes the Sun’ off the album. Very few bands…their most popular album is their last one… Rick Rubin will say the White Album is their best”.

The band would break up three years after Revolver and never work together again. Revolver is a unique artistic statement that has endured the test of time and still sounds as fresh now as it did in 1966. Following Revolver, the next sonic statement of the Beatles was in 1967, and it goes a little something like this:

It was 20 years ago today

Sgt. Pepper taught the band to play

They’ve been going in and out of style

But they’re guaranteed to raise a smile

So may I introduce to you

The act you’ve known for all these years

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band