Released in 1991, Nirvana’s major-label debut is considered one of the most acclaimed albums in the history of music. Stellar* guitarist and producer Chris van de Geer shares what Nevermind meant for rock music at the time and the cultural impact that remains decades on after its release.

When Nevermind first released, Nirvana was already a burgeoning alt-rock band crawling the corners of the underground Seattle music world. Their 1989 record Bleach had made them a favourite among misfit college kids and while it took its influence from a sludge metal sound familiar to the area, the band were starting to find themselves unintentionally becoming the figureheads for a grunge movement that was beginning to rumble. Fresh off the overdramatised glitz of the 80s, the allure of grunge and bands like Nirvana provided a whole new generation of teens a safe space to be their misunderstood selves, away from the prying eyes of adults. This, of course, was a shift that would change the world, but it was never really one Nirvana planned for. “You know, they didn’t change,” offers Geer, when asked about the impact of it all. “Nevermind is this brilliant album, but it’s no real different from Bleach or even In Utero. People moved towards them. They had finally caught on and were like this music is actually great and edgy, and I think there was something attractive in that that they hadn’t heard in other music before.”

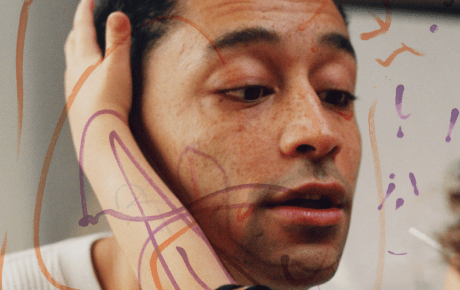

Geer recalls the years surrounding Nevermind’s release well, probably in part due to his first band Second Child opening for Nirvana at their Logan Campbell Centre show in Auckland in 1992. “I had been listening to Nirvana a couple of years earlier, when Bleach was released, and they were just another great underground, on the grunge movement side, band. Then Nevermind sort of went ballistic. I think by the time they came to NZ, ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ had gone to number 1 but we still viewed them as a kind of alternative, underground band, but suddenly they had booked the Logan Campbell Centre with 3000 people, and we got the support.” Second Child were only a short-lived figure in Auckland’s 90s rock scene, with Geer dipping into a number of musical and production projects since (most notably his work with Boh Runga-led NZ pop rock band Stellar*), but he looks back on that ’92 gig as if it was yesterday.

“It was a big deal for us to play, we had never played at a venue that size or with that level of production, and then there was also that great thing of going cool, I get to see Nirvana for free!” Geer smiles. “But it really was awesome. A lot of people were vying for the support, so we were stoked to get it.”

It would be two years after that show that Kurt Cobain would die tragically, cutting the lifespan of Nirvana to an ephemeral five years. Their legacy, however, would see them join the list of the biggest bands in history. Rarely has there been an artist or group whose career has seen its biggest heights in its aftermath and in Nirvana’s case, a whole new division of the band and everything it stood for. I wanted to know what that must be like for someone like Geer who has had a foothold in both worlds, the one where Nirvana exist simply as they are, and the other where their distorted smiley face logo has become just as recognisable in pop culture and consumerism as the Nike Swoosh (and where Dave Grohl is more famously known for a completely different band). Somehow over the years, Nirvana seemed to turn into the very thing they were against, but with only a short-lived career span, can we really blame new generations for the post-Nirvana world they were born into?

“You’re totally right, the brand of Nirvana is almost more important than their music,” Geer agrees. “I think it stands for a few things; for younger kids who got into it, who were probably about 15/16 at the time, Nirvana was probably an incredibly important band to them and then [you have] the older, straighter crowd who were into the rock side of stuff liking them too, because it was produced so well and it was palatable for them.” The filtration of Nirvana is one of the most fascinating things about them, the idea that they can mean something to anyone of any age, from any generation. There’s a bond there that ties even the 13-year-old girl with Nirvana on her Spotify playlist to the 50-year-old man with his original pressed record from 1991. It’s that point exactly that explains why Nevermind has performed the way it has over the years.

“I think there’s a time in teenage years where music is the most pivotal point, where a lot of those influences you listen to for life are formed,” Geer continues. “And I think at some stage, because you know, there’s a lot of mainstream and commercial music, everybody might flitter with listening to something more on the left. You come across Nirvana and there’s something infectious about the energy in it, and at some point, that energy will resonate with you.”

As for their influence on rock music, Geer cites Nevermind as really being the catalyst for the modern sound that followed. “It bridged that gap between early alternative American punk to what can be an edgier, mainstream rock record. It really influenced everything. I mean, many years later you have someone like Matchbox Twenty, who wouldn’t be the same way without Nirvana. They might’ve merged more 70s Americana rock with it, but the production side of that stuff wouldn’t have evolved without Nevermind bridging that gap for everybody.”

I ask about his thoughts on the punk resurgence that’s become trendy over the last few years; in almost an ironic way, teens of today are fighting back at the mainstream while simultaneously becoming exactly that. You can hear the slashing guitars in pop songs on the radio and witness the same nonchalant energy and DIY fashion, but is it all just the same pattern? “There’s always been waves and I think that’s just gonna be a constant thing. It comes from people being young and not having experienced anything or [having] seen a live band with four guys on stage just making a racket. You might see that or hear that in a record and again, I think it has a real primal resonance with you.”

The rawness of Nevermind certainly sticks with you. The album plays like a portrait in a broken mirror; the pieces all technically make a picture but you just can’t quite make it out through its distortion. From the catchy pop hooks hidden beneath crashing drums to the delicately placed acoustic strings, Nevermind was certainly nothing that had ever been heard before. “It was a brilliant album because it had a lot of the dynamics and pop sensibilities of the Pixies, but it was a really grunty rock record as well. You could hear their alternative punk influences, but it still had a lot of energy, so it was kind of a ground-breaking record in a production front as well.” When I ask what track Geer wishes he could have written, his answer gives no hesitation. “I’d have to go with ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ because the riff of it is so good. You’ve got this great thing with the verse and the guitar, and I think that’s the moment where you’re hearing that Pixies influence. The verse is kind of gigantic, you know?”

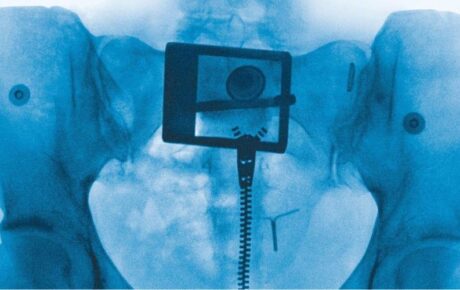

Thirty years on, Nevermind remains not only a spectacular record, but an emblem of a cultural shift it never asked to be part of. The album’s cover, a naked baby swimming after a dollar bill on a fishing line, has become one of the most famous album covers of all time. It’s sold over 30 million copies worldwide and was added to the National Recording Registry in 2004 for its “cultural, historical and aesthetic significance.” It’s all not a bad effort for a group of twenty-somethings clashing guitars in their basement, but you can’t help but notice the irony of it all. What started as an underground haven for outsiders has since evolved into one of the biggest trends in history. “It wasn’t by their own doing, their music didn’t change. But you know, Nevermind and Red Hot Chilli Peppers’ album, Blood Sugar Sex Magik, were released the same day,” Geer says. “Those two records kind of signify when that underground moved into the mainstream with sales and awareness, and got accepted by the normal rock crowd as opposed to an alternative underground crowd.”

As someone who was born three years after Cobain’s death, and is therefore accustom to the merchandise of Nirvana in the world that exists now, I explain how fascinating it’s been talking to Geer about an album we’ve both loved at different points of our lives. The views of him experiencing it first-hand to my discovery of its infiltration through pop culture, to the current 13-year-olds just now adding its tracks to their playlists. I share how incredible it is that an album can transcend generations like that. “That’s the great thing about Nevermind, it catches the rawness of them,” Geer concludes, bringing us back to that magical night in ’92. “And on that night, it really was just those three guys on stage making a racket.”

SEE ALSO: ‘Adrenalize’: How Def Leppard Gave 90s Rock A Shot In The Arm