It’s not often remembered now, but disco-tinged groups such as Bee Gees and ABBA were once the enemy: the birth of disco and the dominance of the four-to-the-floor beat was regarded by some rock fans as a plague on mid-70s music. There were events where disco records were smashed, much as hellfire preachers shattered rock’n’roll singles in the mid-50s. Rock was good, disco was bad. And never the twain should meet… Except it wasn’t that simple.

Disco had grown up on the US East Coast, stepping out of black clubs and sneaking up on pop almost unnoticed. African-American acts such as Hamilton Bohannon (“South Africa Man,” “Disco Stomp”), The O’Jays (“992 Arguments,” “I Love Music”) and Eddie Kendricks (“Keep On Truckin’,“Boogie Down”), to name but a few, produced credible, funky, highly-arranged music aimed at the dancefloor with a disco beat. By 1974, Barry White was delivering symphonies of disco-soul for himself and Love Unlimited, and the likes of KC & The Sunshine Band and Gloria Gaynor were cutting music designed for DJs to move the crowds with the minimum of effort.

While critics raved over rock and the kids wore greasepaint for glam, an audience that was old enough to go clubbing danced to disco. The charts filled with music driven by four bass-drum thuds to the bar, and, unlike funk, the rougher groove that claimed to be the sound of black rebellion when delivered by the likes of Parliament and James Brown, disco was rhythmically simple to master. It was only a matter of time before white pop bands decided to turn their hands to it. The most obvious example were three Mancunians with Australian accents: Bee Gees.

It was a perfectly logical move for the brothers Gibb. Chart fixtures since the second half of the 60s, the group were looking to retain their prominence as the 70s drew to a close. Their remarkable one-size-fits-all material had been heavily covered by soul singers such as Al Green (“How Can You Mend A Broken Heart”) and Nina Simone (“To Love Somebody,” initially intended for Otis Redding), so they were no strangers to groove. In 1975 they cut Main Course, an album that delivered two hits, “Jive Talkin’” and “Nights On Broadway.”

This was not audio junk food: these were highly accomplished records with an evident understanding of the genre. Further disco material populated their 1976 album, Children Of The World, which boasted the US No. 1 “You Should Be Dancing.” Disco had ushered in a new phase of the group’s career and, in return, Bee Gees gave disco much of its enduring soundtrack for Saturday Night Fever, songs that made a downbeat 1977 movie an unanticipated smash. “Stayin’ Alive,” “Night Fever,” “More Than A Woman”… here was disco’s high-water mark. The movie made John Travolta a star, and suddenly paunchy men who should have known better were copying his chest-out, hand-pointing-into-the-air pose at wedding receptions. Disco was mainstream.

Frankie Valli had also been quick on the uptake. In 1975-76, with and without his group The Four Seasons, he hit with “Swearin’ To God,” “Who Loves You,” “December 1963 (Oh What A Night)” and “Silver Star,” which all bore disco’s hallmarks. The sound was everywhere, and the Billboard charts at the back end of 1976 were dominated by a series of disco-driven No.1s such as “You Should Be Dancing,” Wild Cherry’s “Play That Funky Music,” Walter Murphy & The Big Apple Band’s “A Fifth Of Beethoven” (an early incarnation of forthcoming disco leaders Chic) and radio comedian Rick Dees with A Cast Of Idiots delivering “Disco Duck,” the most successful of many songs mocking the genre. Rather more dignified, ABBA grabbed a worldwide No. 1 with ‛Dancing Queen” – nailing yet another genre of pop without losing their fundamental character, as ever.

Disco raged on through 1977: former clown-dressed British singer Leo Sayer found a US No. 1 with “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing” and also hit with the more soulful “Thunder In My Heart”; US vocalist Donna Summer, with the assistance of German producer Giorgio Moroder, made the electro-disco monster “I Feel Love.” The following year saw Barry Manilow barking “Copacabana,” and Blondie brandished their New York clubland affiliations through “Heart Of Glass.”

They weren’t the only “new wave” band to “go disco.” Ian Dury & The Blockheads’ two biggest hits, “Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick” and “Reasons To Be Cheerful Part 3” were both fundamentally disco tunes; little wonder that Dury’s writing partner Chaz Jankel’s “Ai No Corrida” became a hit for Quincy Jones, the jazz-funk bandleader who’d produced numerous disco smashes for Michael Jackson, George Benson and The Brothers Johnson.

Disco was the first dancefloor phenomenon where you didn’t have to be black to create credible records. The Rolling Stones and Rod Stewart tapped into it for chart successes with “Miss You” and “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy.” ELO’s “Evil Woman” and “Turn To Stone” were both disco without compromising the band’s essential sound; few noticed when their 1979 hit-packed album was called Discovery. Disco, very – geddit?

The disco backlash peaked in 1979 with “Disco Sucks” T-shirts becoming briefly popular among rock fans who objected to “their” bands coming second to those that incorporated disco elements. Hardcore punks Dead Kennedys released “Disco Holocaust,” and some fans wrongly assumed that PiL’s “Death Disco” was actually called “Death To Disco,” another slogan used by objectors.

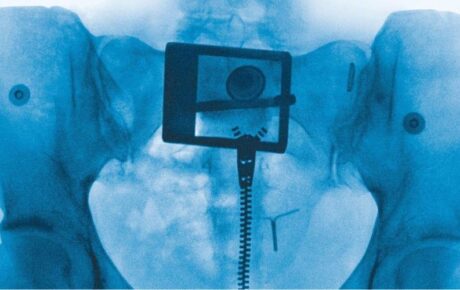

In July that year, Disco Demolition Night was a well-publicized event organized by two DJs at a baseball match in Chicago, featuring a truck full of disco records being blown up on the field. This foolish act damaged the playing surface and prevented the match that had been meant to follow it from going ahead. But the music danced on, with LA’s SOLAR records roster, which included Shalamar, taking the sound to new heights. Chic influenced Queen’s 1980 smash “Another One Bites The Dust,” Barbara Streisand duetted with Donna Summer, and even The Kinks, J Geils Band, and KISS included dancefloor elements in their records.

Disco had first become a definable musical culture at US East Coast clubs such as Larry Levan’s Paradise Garage; it peaked at the louche Studio 54 night spot in Manhattan, at which Grace Jones was a regular fixture, and it was in New York that its demise became apparent. Ghetto kids sought a harder-edged, more streetwise dance music and found it in hip-hop, which steadily drove disco off the agenda.

But it’s worth bearing in mind that many early hip-hop releases were recorded live in the studio by bands approximating disco’s good-times grooves. Sugar Hill Records, the label most associated with the birth of hip-hop, initially saw this music as an offshoot of the black disco music its parent company, All Platinum, had specialized in, and the subsequent electro offshoot owed plenty to four-to-the-floor music.

White pop shrugged off its adopted disco sound around the early 80s, regarding it as a tool whose time had passed… or did it? Even if they lacked the glitz of disco’s peak, records such as Gary Numan’s “Cars” and the majority of hits from Soft Cell and The Human League were mixed for club play. More recently, Katy Perry paid due deference to the music with mirrorball-loaded teasers for her single “Chained To The Rhythm,” while, bringing things full circle, Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive” was remixed by DJ Getdown in early 2017, showing that truly timeless groove will always fill the dancefloors.

Death to disco? Nah. Long live disco.

Article originally published on uDiscoverMusic.com.

SEE ALSO: ‘Size Isn’t Everything’: How Bee Gees Remained Big In The 90s