It’s 3pm on Easter Monday, 1979 in Auckland, Aotearoa; and arguably one of the most important musical artists of the 20th Century is about to take the stage to perform his first and sadly last concert at Western Springs Stadium.

By this point, Bob Marley and his band the Wailers are well established as one of the biggest reggae artists in the world, by mixing reggae, ska, and rocksteady to create their unique sound. A mere 40-so years later, not only has the significance of Bob Marley lived on but our country owes a lot to both the star’s legend and his music.

In recognition of the 1979 concert’s significance and its impact, TVNZ has produced a brilliant docuseries called When Bob Came that investigates the impact of Marley’s trip to Aotearoa and the cultural impact on our Māori, Pacifika and progressive Pākehā. The effect of this concert sent cultural shock waves throughout the country and people started to recognise the need for their own uprising in Aotearoa. It could be argued that Bob Marley’s impact was never felt more strongly than by the Māori and Pacifika community in Aotearoa. His music and his ethos is so deeply steeped in our DNA, from our casual use of Marijuana to our local sound, that one of Marley’s greatest contributions to the country can be heard and felt from that day to now.

So what does When Bob Came teach Aotearoa?

The Concert

The docuseries When Bob Came is presented in six parts. The first episode focuses on the concert itself.

In 1979, Aotearoa had been mostly under a National Government for 30 years. Except for two brief periods of Labour governments in 1957–1960 and 1972–1975, National would hold power until 1984. The relationship between Māori and Pacifika versus their colonists was heading towards a boiling point and by 1979 the timing was ripe for change or war. It was at this time that Bob Marley announced he’d play one show at Western Springs Stadium in Auckland (for just $8.70 a ticket!).

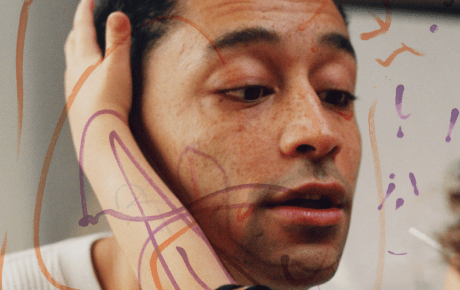

The concert at Western Springs proved that an act of revolution can be a man with a song bearing the message of unity in the fight against oppression. Marley inspired hope and determination, preaching peace, love and resistance to a crowd of 22,000. Tigi Ness, founding member of the bands Twelve Tribes of Israel and Unity Pacific, described the concert as a “Reggae Revolution” and Aotearoa was prime for this revolution at the time. Ché Fu, Ness’s son who attended the concert at only 4 years old with his parents (despite there being an age restriction of attendance for 20 years and over) commented, “He was singing about pain and suffering that we could directly relate to.”

Bob Marley was the first international artist to really sink into Aotearoa’s culture and change it. James Rolleston who narrates the series describes Marley as a “myth or legend from a long time ago.” Before Bob Marley arrived in Aotearoa, his music and message had already become the soundtrack to protests and politics here. Upon arriving at their hotel, Marley and his band were greeted with a powhiri, which was usually reserved for dignitaries. Marley loved the ceremony and was really into it. Ness described the powhiri as a “spiritual awakening” and went on to say that the moment the powhiri had finished, the sun came out.

When asked about the gig prior to taking the stage Marley said, “Tonight we are playing with a purpose… our message is a good vibration, that all people must come together.” He walked onstage in blue denim and his iconic dreads and his first words into the microphone were “Came a long way, one nation under one roof. It’s a Rasta man vibration!” The band opened with the song ‘Lively Up Yourself’ and Fu recalls, “I remember looking out into the crowd and seeing a lot of happy people.” Ness described Marley on stage as “not a big man physically, but he had this massive aura around him which was like a spiritual awakening.”

“When Bob came it was kind of like someone had sent reinforcements to come help us fight the colonial miseducation. When Bob came, Māori men had a role model that was speaking love and life and fight. When Bob came it changed a lot of things in my life,” quotes key hip-hop pioneer Darryl ‘DLT’ Thomson.

This was a concert for the history books.

The Music

The second episode of When Bob Came moves the focus to the music of Bob Marley. Not only did Marley change how we listen to music but also how we created it, and he is perhaps the biggest influence on contemporary music in Aotearoa ever. His greatest hits album Legend, released in August, 1984, become one of the biggest selling albums in our country’s history, spending three years at the top of the charts and selling over 300,000 copies.

Marley’s influence on our music can be traced through the decades as each generation discovers his music. “Nobody could deny that Bob’s music was winning people over, it was part of that uplifting energy because it was music we could take away with us,” states Ness. When one reflects on the development in Aotearoa’s music from 1979 until now you can draw a direct line of inspiration from the concert. It’s a hybrid of a hard political message with a sweet melodic melody, the way Marley had done to deliver an effective message.

Early reggae bands like Dread Beat & Blood, Chaos, Herbs and the Twelve Tribes of Israel were ready to satisfy audiences who were hungry for reggae, with each band having a deep political and spiritual message behind their music. Members of what would become one of Aotearoa’s greatest reggae band, Herbs, were at the concert. Founding member Toni Fontoni described the experience, “The greatest influence Bob Marley had on me was to become a messenger, really he changed my life. I wanted to make music to empower people so they could stand up and feel strong.” Their biggest hit was a song called ‘French Letter’, a protest song about the nuclear testing in the Pacific.

Marley once stated his music taught the indigenous cultures the three R’s; Reggae, Rasta and Revolution, and never would this be more evident than in the music created by the next generations. In 1997, DLT and Ché Fu would release their smash hit ‘Chains’. That, accompanied with the incredible success of his 2001 album Navigator, catapulted him to his now legendary status in the music of Aotearoa and our indigenous and Polynesian people. Fu acknowledges that Marley’s music definitely inspired him and stated, “I’m sure I have ripped off plenty of bass lines from that guy.”

As time went on the band Katchafire emerged from Hamilton, who started as a Bob Marley cover band. With the release of their debut album Revival, a new music scene was born in Aotearoa that took us into the 2000’s and the then developing Dub/Reggae sound. Then the music really started to flow… Trinity Roots, Fat Freddy’s Drop, Tiki Taane, Kora, Cornerstone Roots, The Mercenaries, Energy Rising, Black Seeds, Fly My Pretties, Barnaby Weir, Salmonella Dub to name a few acts and then more recently Six60, LAB and Troy Kingi.

Kingi reflects, “When I think of Bob, he was the best songwriter, he was the master of having the perfect amount. The perfect balance of melody and everything just sitting in the pocket. I try to follow in his footsteps when it comes to crafting really well-crafted songs”.

Tiki Taane describes Marley’s influence on music in Aotearoa as, “He was more than a musician, he was a prophet and he spread the message of music. He was a very powerful inspiration for a lot of us here.”

The Protest

The third episode of the series switches the focus to the subject of Protest. The music of Bob Marley inspired a movement and gave clarity to Māori and Pacifika people to rise up and fight for equality and have the Crown recognise their mana. In 1974, Bob Marley released his album Natty Dread, with the song ‘Them Belly Full (We Are Hungry)’, which said it all for Māori. A year later, 50 people set out from the far north of Aotearoa and walked over a thousand kilometres on a hikoi to Parliament to protest the sale and confiscation of Māori land, led by a 79-year-old Dame Whina Cooper. The number would grow to 5000 by the time the march reached its destination.

Māori owned all the land in Aotearoa in 1840 at the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. However, by 1920 they only owned eight percent. The Pākehā had seen the land as a commercial enterprise whereas the Māori saw the land as their soul. But while tangata whenua fought for their land, the Pacifika immigrants were fighting their own injustice. They were being subjected to a government campaign to remove all overstayers and send them back to the islands with dawn raids at their residence.

With more and more racism facing the Pasifika community, the Polynesian Panthers formed in 1971 and aimed to stand up for their community’s rights, among them the then-17-year-old Tigi Ness who became their Minister of Culture and of Fine Arts. In 1978 the Crown claimed the land at Bastion Point, taking it away from the rightful owners Ngāti Whātua, which became the catalyst of the now infamous 506-day-protest.

Marley’s concert coincided with the fallout of Bastion Point, along with increasing concern about nuclear testing in the Pacific. Aotearoa was ready for a revolution. In the aftermath of the Springbok 1981 tour, Tigi Ness was sent to Mt Eden prison for nine months over protests. “It was Bob Marley’s music that got me through prison,” he says.

In 1987 Te Reo was established as the official language of Aotearoa and in 1997 the Crown signed a Deed of Settlement that provided compensation valued at $170 million to Ngāi Tahu. Things that had seemed impossible were starting to be achieved. The voices of the oppressed had been heard and change was all around, in small part thanks to Bob Marley’s music.

Marley’s music and his message fueled a revolution. Fu recalls “My father used to read a lot and I would hear these names – Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and Huey P. Newton. But it’s different when you see a man and he sings and you listen to his music over and over, day after day, and then he comes to your country. It’s a whole different level of significance and that sort of stuff stays with you.”

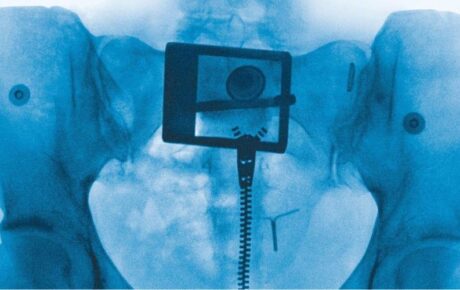

The Ganja

The fourth episode looks at the role of Weed or Ganja in our culture and its relationship to Rastafari and Bob Marley’s music, as well as the drug history in Aotearoa.

For millennia, marijuana has been valued for its use for fibre and rope, as food and medicine, and for its psychoactive properties for religious and recreational use. In the middle of the 20th century, international coordination on a war on drugs led to sweeping restrictions on weed throughout most of the globe.

In 1971, the United States passed the Controlled Substances Act, prohibiting cannabis federally along with several other drugs. Richard Nixon’s declaration on the war on drugs swept through the western world like a plague. As country after country fell to the conformity, they punished users with jail time and treated wisdom weed smokers as criminals. Weed was portrayed as evil, a destroyer of communities, and a gateway drug to harder substances; and Aotearoa was no exception.

But Bob Marley’s message was different. Cannabis was and still is used by Rastafarians to heighten feelings of community and to produce visions of a religious and calming nature. Rastafarians are unlikely to refer to the substance as marijuana; they usually describe it as the wisdom weed or the holy herb. Today in Aotearoa there are less than 1000 cannabis convictions a year. However, in 1980, there were over 120,000 cases of possession for cannabis. In 1979 when Bob Marley arrived, the country was very much in two camps on the use of weed. The authorities had zero tolerance, whilst for others smoking herb was part of everyday life. Thomson recalls, “ I remember the time before weed, it was drink this brown stuff until you feel angry. Herb changed the whole dynamic of everything.” With the increased use of weed people finally felt they had a passionate supporter for this tool of enlightenment.

For many of the peaceful crowd who had made the journey to Western Springs, weed was a big part of their experience. Marley represented to people a freedom and acceptance of the unaccepted within the greater society. This was a very powerful statement for the people of Aotearoa in 1979 and made them think again about the legal status of cannabis in our country. Marley was shedding light on the positive aspects of smoking weed and he was unshakable about it, as well as his fight to lift prohibition.

The Rastafari

The fifth episode covers the spiritual practice of the Rastafari. Rastafarian beliefs are based on a specific interpretation of the Bible. Central is a monotheistic belief in a single God, referred to as Jah, who is deemed to partially reside within each individual.

When Bob Marley arrived in Aotearoa he brought more than just music, he brought a faith. The Rasta movement in Aotearoa began with the Twelve Tribes of Israel in Auckland and challenged colonial views of Christianity that would reclaim the bible with a new prospective and a new messiah. But fear of the faith’s practices and systemic racism saw members persecuted. By the 80s, the country at this time was viewed as a Christian based country and the Polynesian community already had a strong relationship to the faith and Jesus Christ. However, the general depiction of Jesus Christ at the time was white.

The presence of Marley in Aotearoa was the beginning of a curiosity that developed into practice and then a movement. The new anti-colonial faith spoke to the oppressed and offered empowerment. When Marley arrived he brought more than music, he brought a new way to interpret the scriptures. Rasta emerged from the impoverished areas of Jamaica, it was a faith of the oppressed that resonated here. Thomson explains, “I come from a fatherless generation of Māori kids and this guy [Marley] became Dad.”

The Rasta movement is not a dogma religion, but rather a freedom and a spiritual life that has made Aotearoa a better place with its presence and ideology. It could be argued that outside of his music, Rastafarianism is Bob Marley’s greatest contribution to our country.

The Cultural Pride

The final episode of the series focuses on cultural pride. The racism and dishonouring of the Treaty of Waitangi left Māori with a stifled and oppressed sense of self. The issues seemed too insurmountable to overcome. But for many, a lot of that changed that day in 1979 at Western Springs.

The event itself and the message behind the music gave everyone a sense of hope. The willingness to dream of a better country, a country for all not just for some. A country that would recognise and celebrate its roots to honour the tangata whenua of Aotearoa. The desire to reignite the language of Te Reo and have it seep its way back into daily life of Māori; to be spoken without fear or a sense of persecution and reconnect with their roots. A native tongue to lift the message of the Māori to not only Aotearoa but the world.

The cultural significance of Bob Marley’s concert is so far beyond the actual event itself that it still resonates to this very day. It is ever present in the music of Aotearoa and can be heard throughout the back catalogue of all our music. The music is our roots; to hear it, all you need to do is open your mind.

So where is the legacy of Bob Marley now? Marley has evolved into a global symbol, which has been endlessly merchandised through a variety of media, but his legacy in Aotearoa is revered and has escaped the watering down effect. What makes us different is that even all these years later, there is still deep mana held for the true essence of Bob Marley’s message and music.

In Aotearoa the political tides clearly started shifting after the concert at Western Springs. The indigenous Māori started to find a voice and a fight that would be heralded around the world. Bob Marley would have loved this defiant stand by Aotearoa’s people. He would applaud Māori for standing up for their rights, for reconnecting with their roots and being unapologetic of their culture. Praise Jah! This is what we, the people of Aotearoa, have learned from Bob Marley.

The docuseries When Bob Came is a must watch for the fans, the curious and the dedicated. It is beautifully written, filmed and edited. The series is easily one of the most brilliant deep dives into a hugely significant moment in Aotearoa’s musical and spiritual history. Don’t miss it! So go lively up yourself, roll something green, drop the needle on a piece of Bob Marley vinyl and dig deeper into the beauty that is, was and will forever be… Uncle Bob’s music.

When Bob Came is a six-part docuseries available to stream on TVNZ+. Watch it in full here.