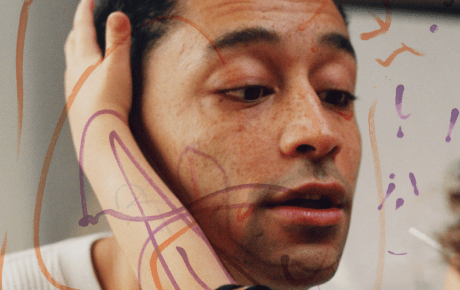

The critical and commercial success of Kendrick Lamar’s second album, 2012’s Good Kid, MAAD City, totally changed the Compton rapper’s life. He had gone from a respected artist with a decent-sized, devoted fanbase to an award-winning, multi-platinum writer considered by some to be the voice of his generation. The album was a nuanced, multi-faceted account of Lamar’s upbringing in Compton, its vivid vignettes on gang violence, institutional racism, street politics, costly mistakes and dead-end disillusionment the stuff of gritty Hollywood fare. And it came in the shape of thrilling, straight-shooting West Coast hip-hop, with Lamar’s dexterous wordplay and nimble approach to voicings elevating it to another level. Three years later, then, when To Pimp A Butterfly was finally ready for release, expectations were extremely high.

The first taste of Good Kid…’s follow-up was released in September 2014 in the shape of the Isley Brothers-sampling ‘i’. An upbeat slice of radio-friendly funky hip-hop, it preached a positive message of self-love and celebrated individuality, but seemed perhaps lighter than many had expected. When To Pimp A Butterfly was released on 15 March 2015, the song was an intrinsic part of the sprawling narrative Lamar unfurled. Now sounding tougher and more vital than before, it included a speech from Kendrick mourning the effects of gang violence and urging black communities to celebrate themselves.

It showed fans there was no second-guessing Kendrick – especially not in a musical sense. To Pimp A Butterfly sounded unlike anything Lamar had done before: a genre-busting jubilee in honour of the funkiest, freshest and most out-there elements of African-American music. He assembled a crack band of the most exciting jazz musicians of the day, installing saxophone colossus Kamasi Washington as musical director.

It was as if Lamar sought a music that could tell the story of black America as vividly as he would in his lyrics; a music that was as free-flowing and supple as his verses. And this wasn’t some fusty, old-fashioned take on jazz. The most forward-thinking jazz musicians of recent times have had hip-hop coursing through their veins, as Washington has said: “We’ve grown up alongside rappers and DJs, we’ve heard this music all our life. We are as fluent in J Dilla and Dr Dre as we are in Mingus and Coltrane.”

Among a plethora of gifted musicians at Lamar’s disposal were pianist Robert Glasper, the producer/horn player Terrace Martin, guitarist Marlon Williams and bass virtuoso Thundercat – all incredibly versatile players, as adept at turning their hand to the deep funk of ‘King Kunta’ as they were to the chaotic free jazz excursions of ‘u’, or the lush, Prince-like slow jam of ‘These Walls’.

Lamar’s narrative was just as ambitious. It’s an intense exploration of big themes: exploitation, living up to responsibilities, the importance of staying true to yourself, finding strength in the face of adversity. Over the course of To Pimp A Butterfly he tells the story of a rapper finding fame; learning how to “pimp” his talent for material gain; dealing with the temptations that accompany fame and wealth; feeling the burden of his new position of influence; turning to black history and his roots to try to find guidance; dealing with a kind of survivor’s guilt after leaving his people; and eventually finding the self-belief and wisdom to share with his community.

But the album is nowhere near as tidy and linear as that sounds. As complicated as the subject demands, To Pimp A Butterfly’s songs are crammed with deep dives into US history, and just about every lyric has the listener conflicted as to the narrator’s motive (and, sometimes, even the identity of the narrator).

All of this would be worth little if the album didn’t communicate all of its ideas effectively. Somehow, however, To Pimp A Butterfly does that brilliantly. A thrilling, genuinely affecting and often awe-inspiring ride through Lamar’s psyche, it resonated with enough people for its influence to be felt everywhere: the hope-filled ‘Alright’ was adopted as the unofficial anthem of the Black Lives Matter movement; there were stories of teachers playing the album to students to help them better understand the oppression faced by African-Americans; listening to it influenced David Bowie to move in a jazz-inspired direction on his final album, ★.

With To Pimp A Butterfly, Kendrick Lamar delivered on expectations and then some. It remains a visionary, landmark album that will resonate for generations to come.

Article originally published on uDiscoverMusic.com.