Released in April 1973, Catch A Fire did for reggae what Please Please Me, the first Beatles album, had done for pop and rock exactly a decade earlier. An album of revolutionary genius, which combined perfect timing with lasting cultural significance, Catch A Fire laid a foundation stone for the career of the world’s first and indeed only reggae superstar and established a bridgehead between the deep roots music of Jamaica and the commercial pop mainstream of the First World. Its release marked the moment that reggae truly did begin to “catch fire” on the international stage.

Although Catch A Fire introduced Bob Marley to the world beyond his Caribbean homeland, it was not the singer’s first album. Indeed, it wasn’t even a Bob Marley album. Catch A Fire was the fifth album by the group known and billed simply as the Wailers who had been playing and recording together in Jamaica for a decade or more before it was released.

It is difficult to convey how little was known about Jamaican music in pre-Marley Britain and America at the start of the 1970s. Despite the rich and varied history of reggae and its antecedents of ska, bluebeat and mento, only a smattering of reggae songs had ever made an impression on the charts outside the island. In the UK, reggae had unfortunate associations with the skinhead boot-boy tendency and Max Romeo’s lubricious (and banned) Top 10 hit ‘Wet Dream’. In the US, occasional pop hits by American acts such as Neil Diamond (‘Red Red Wine’) and Johnny Nash (‘Hold Me Tight’) skimmed sweetly across the surface of the reggae/rocksteady tradition.

But this was about to change. The Harder They Come, a movie starring the Jamaican singer Jimmy Cliff, with a soundtrack of reggae songs performed by Cliff, Desmond Dekker and others, premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 1972 and became a slow-burning international success. Later the same year, Nash scored a Top 15 hit in both the UK and the US with his recording of Bob Marley’s song ‘Stir It Up’. The American star brought the Wailers over as support act on his 1972 tour of the UK, where the band met up with Chris Blackwell who signed them to record an album for Island Records.

The Wailers recorded Catch A Fire in three different eight-track studios in Kingston. In contrast to previous recordings, they now had a budget that could do full justice to the songs, seven of which were written by Marley – who also produced the album – and two by the group’s other singer and lead guitarist Peter Tosh. Even so, when Marley returned to London to deliver the master tapes, Blackwell insisted that more work was needed and promptly took over the production reins. Adding overdubbed contributions from the session guitarist Wayne Perkins, Blackwell tweaked arrangements and adjusted mixes, rolling back some of the heavier bass-end parts and generally moulding the sound into a shape that remained true to the band’s roots, but which would also sit comfortably in the mainstream rock marketplace of the day.

The result was an album with a groove that was languid, soulful and sun-drenched, yet lean and taut as a coiled spring. The bass and drum parts – supplied by Aston “Family Man” Barrett and his younger brother Carlton Barrett, respectively – were welded together by the distinctive staccato scratch-strokes of Marley’s rhythm guitar. The irresistible rhythmic tug which this produced was a revelation to the great majority of listeners discovering the band for the first time. So too were the incredibly intricate vocal parts. It is often forgotten that the Wailers had begun life as a vocal group and now, aided by Rita Marley (Bob’s wife) and Marcia Griffiths, the band, including percussionist Bunny Wailer, wove a rich patchwork of harmony and counterpoint vocal parts around Marley’s and Tosh’s melody lines on numbers such as ‘Stop That Train’ and ‘Baby We’ve Got A Date (Rock It Baby)’. The keyboard parts, supplied by John Rabbit Bundrick, completed the sonic picture with organ, clavinet and a sprinkling of modern electronic effects.

SEE MORE: Bob Marley 75 Birthday Anniversary Celebrations

It was an album of two sides; literally, in those days when vinyl was the only commercially-viable format, but also in its lyrical preoccupations, which were evenly divided between a cry of anguish from the ghetto and the cry of a young man in pursuit of something else. The album’s most enduring song, ‘Stir It Up’ – already a hit for Johnny Nash – was followed by the even more explicitly amorous ‘Kinky Reggae’, in which a certain Miss Brown was said to have “brown sugar all over ’er booga-wooga.”

But the emotional meat of the album was in the passionate, street-poet lyrics of protest songs including ‘Slave Driver’ and ‘400 Years’. “No chains around my feet/But I’m not free/I know I’m bounded in captivity,” Marley sang in ‘Concrete Jungle’, the first of several searing cries on behalf of the oppressed and dispossessed of his homeland which echoed what used to be known as the “negro spiritual” music of previous generations.

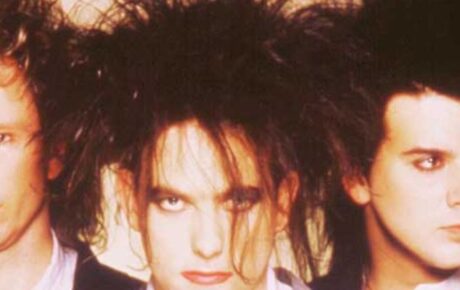

The cover of the Wailers first album The Wailing Wailers, released in 1965, carried a picture of the three principals – Bunny Wailer, Bob Marley and Peter Tosh – neatly groomed in tuxedos and bow ties above the strap-line “Jamaica’s Top Rated Singing Sensations”. Things had changed somewhat by the time the group made their first UK TV appearance on the Old Grey Whistle Test on May 1, 1973. Marley in a blue work-shirt, eyes screwed shut, looked like a young messiah. He was flanked by Wailer on percussion and Tosh in a rasta-coloured beanie hat and rock-dignitary shades playing lead guitar with an extreme wah-wah effect. Alongside keyboard player Earl Lindo, the heavy-duty rhythm section of Barrett and Barrett locked on to the strangely loping groove in a way that had no precedent in UK music. Their performance on the show of ‘Concrete Jungle’ and ‘Stir It Up’ opened the door to a new musical world for an audience accustomed to a diet of Jackson Browne, Focus and Manfred Mann’s Earthband. With exposure for popular music of any kind still a rare occurrence, it became one of those pivotal TV moments, rather like the first appearance of David Bowie singing ‘Starman’ on Top Of The Pops the year before.

The exotic provenance of Catch A Fire contributed to the indelible impact it had on anyone and everyone who was paying attention. But by the same token, the battle for mass-market acceptance was not to be won overnight. Incredibly in retrospect, the album made no impression on the UK chart and only reached No.171 in the US.

A more appropriate indicator is that Catch A Fire now stands as the highest-placed reggae album in Rolling Stone’s list of The 500 Greatest Albums Of All Time (at No.126; it was outranked only by Marley’s posthumous compilation Legend at No.46). But whatever the statistical data may or may not suggest, it is difficult to overstate the historical importance and groundbreaking brilliance of Marley’s first international album release.