‘Redemption Song’: it seems everyone who is into music knows this song. It is Bob Marley’s anthem of anthems, a testament passed to us at the end of his life to remind us how we had arrived where we were, just what we would be missing when its singer was no longer around, and to help us carry on in his absence. If that sounds like an exaggeration, search online: there are countless thousands who use Bob Marley’s music to keep them keeping on through the demands of a harsh and difficult life.

“Emancipate yourself from mental slavery”

The idea that songs can bring redemption has echoed down the centuries. The wretch that was saved in ‘Amazing Grace’ was rescued from Hell by a song – “how sweet the sound”. The appalling crime he’d committed was the same crime that afflicted Bob Marley in his ‘Redemption Song’: the writer of ‘Amazing Grace’ was a slaver; Bob Marley was a descendant of slaves. Marley’s songs set him free, made him somebody – though he was well aware of the mental slavery that can still exist even when you are said to be free.

While ‘Redemption Song’, in which Marley accompanies himself alone on an acoustic guitar, is often regarded as an exception in the singer’s canon, it is not an aberration. Bob, like most musicians of his generation, was influenced by the folk boom of the early 60s. He was aware of Bob Dylan, and his group, The Wailers, adapted ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ for their own ‘Rolling Stone’. For poor Jamaicans, the ownership of an acoustic guitar – be it battered, or a home-made “cigar box” instrument – was as much as they could aspire to when it came to musical expression. Marley wrote songs on an acoustic guitar, so every so often a record in a gentler style would emerge from The Wailers’ camp. It was only when he signed to Island in 1973 and could afford to run a permanent electric band that this aspect of his music was largely set aside.

As for ‘Redemption Song’’s lyrics, they, too, followed a familiar pattern, and their theme was by no means a detour from the reggae norm. Marley had connections with artists from Jamaica and the US who wrote songs touching on similar concepts. Bob Andy, with whom Marley had recorded at Studio One in the 60s, touched on the concept of mental slavery in his brilliant 1977 song ‘Ghetto Stays In the Mind’: once you’ve been through a long struggle, it never leaves you. James Brown, the soul man who was a strong influence on Bob Marley in the 60s, spoke of “a revolution of the mind” in an album title and on the final verse of the 1972 anti-drug single ‘King Heroin’, which depicted addiction as a form of slavery. Toots & The Maytals, whose career paralleled that of Bob Marley & The Wailers, without the major breakthrough that Bob pulled off, released the moving but upbeat ‘Redemption Song’ in 1973, calling for release and seeking the words that might please God. And Bob’s anthem quotes from Marcus Garvey, specifically the words “Emancipate yourself from mental slavery… none but ourselves can free our minds”, which are drawn from a 1937 speech made by the black nationalist and Pan-African philosopher and activist, who was born in Jamaica. Bob’s labelmate at Island records, Burning Spear, drew great strength and inspiration from Garveyite teachings – and Spear is an admirer of Bob Marley’s music. In 1978, Bob himself released a single in Jamaica which covered some of the same issues, ‘Blackman Redemption’. So, far from being an exception, ‘Redemption Song’ was right at the heart of Jamaican music and its influences, even though its rhythmic content differed from most reggae.

A last testament

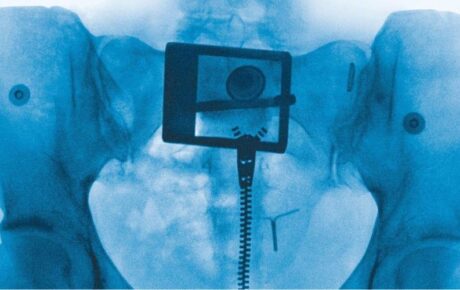

‘Redemption Song’ was a serious composition because Bob knew his time on Earth was severely limited when he wrote it. In the summer of 1977, Bob had been diagnosed with a malignant melanoma under a toenail. He had decided not to have the toe amputated, as doctors had suggested. Bob carried on touring, writing and recording, but within two years he was ailing, appearing gaunt compared to the buoyant star of the mid-70s. Death was on his mind; his wife, Rita, has said he was in severe pain and had been writing material that “dealt with his own mortality… particularly in this song”.

The first recordings of ‘Redemption Song’ feature The Wailers on backing; Bob cut at least 15 versions with his loyal group in 1980. There was also an acoustic take, and several cuts with amended lyrics for use by reggae sound systems, as is usual in Jamaican music. Some of these versions were quite upbeat, utilising what is almost a ska beat.

It was the man who had signed Bob to Island, the company’s boss and founder, Chris Blackwell, who suggested that an acoustic version might have more impact. Bob agreed – and they were right; this song didn’t need embellishment. So it was that an acoustic version of ‘Redemption Song’ became the final track of Uprising, the final Bob Marley & The Wailers’ album released during the singer’s lifetime. A last testament, if you choose to see it that way.

SEE MORE: How Bob Marley’s ‘Legend’ Lives On In Aotearoa

Timeless and inspirational

The song took in Marley’s own feelings about his onrushing sad demise, slavery and its impact on the minds of its descendants, religion and destiny (“We’ve got to fulfil the book”), but did not forget to address his fans. Fear not, the song said. Your existence is not defined by the world powers, by destructiveness, by evil; your purpose is not dictated to by the mighty, but by the Almighty. Your heroes may die, you may be oppressed, you may feel you can’t prevent the wrong things happening, but the universe is bigger than that. Join this song. You have the power to free your mind and soul. You can be redeemed.

Immediately striking in the context of the album, ‘Redemption Song’’s haunting qualities meant its message spread. Cancer claimed Marley’s body in May 1981, 11 months after the release of Uprising. He was just 36. But Marley’s records and image continued to do his life’s work, and ‘Redemption Song’ is now regarded as an anthem of emancipation, up there with the best and most vital records with a message – and, remarkably, it did this without haranguing the listener. A terminally sick man who had grown up in abject poverty delivered a vital message in the most gentle way, and it still reverberates around the world.

Other versions emerged, among them some of the cuts recorded with The Wailers, and many live takes, the most touching of which was recorded at Marley’s final gig, in Pittsburgh, on 23 September 1980. Two days earlier, he had collapsed while jogging in New York City; already seriously ill, the Pittsburgh recording found Bob introducing his masterpiece as “this little song”. Conga drums join him, just as they had in the days of the original Wailers – bass drum playing double time like a heartbeat, like the Rasta drummers who had been at the spiritual core of his music since the mid-60s. This was a performance more than brave; it was timeless and inspirational.

‘Redemption Song’ has been heard in Hollywood movies. It has been covered by Joe Strummer; Stevie Wonder, who was both Bob’s fan and hero; Ian Brown; girl group Eternal; Madonna; Alicia Keys; and John Legend to mark the death of Nelson Mandela… It is a song that resonates with all audiences. And it will continue to touch hearts until the struggles of the poor and the oppressed and the fretful and the unfulfilled end. So you can expect it to play on forever, as long as there are ears to hear, hearts to touch and minds to emancipate.